This is the first in a series of articles about the fallacy of zero sum economics, the idea that if one party benefits, another must necessarily lose.

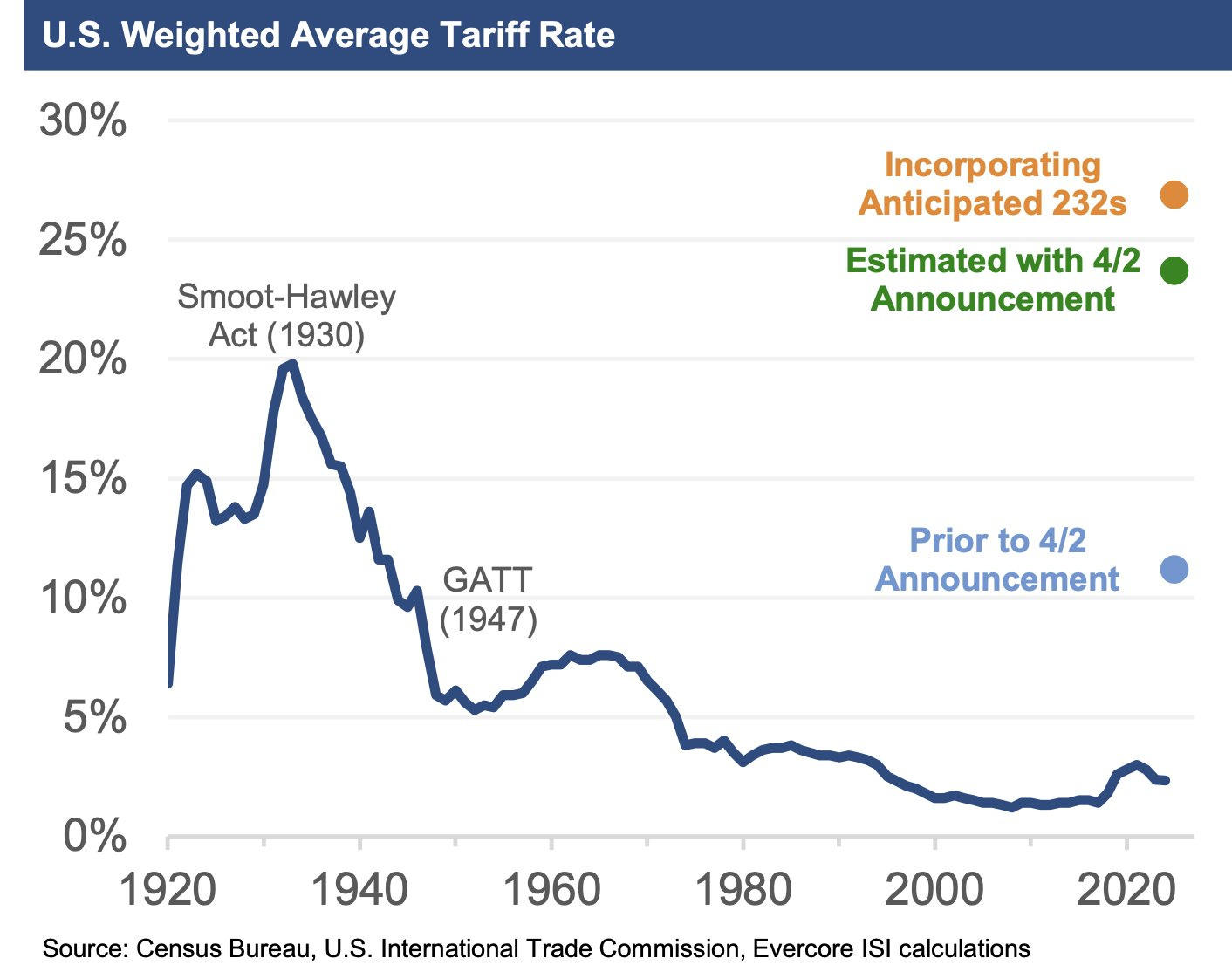

Donald Trump unveiled his fresh batch of tariffs, continuing his attempt to Make America Great Again by making both Americans and foreigners poorer. With the stroke of the President’s pen, the United States has imposed average tariffs in line with some of the poorest, most closed off countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

The catastrophic consequences of these tariffs for domestic consumers, the global economy, and the American-led liberal international order will be well-litigated over the coming days, weeks, months, and years. It is, however, just as important to understand why zero sum thinking, the philosophy underpinning tariffs and economic nationalism is so deeply misguided.

In short, the zero sum fallacy is the idea that if one party benefits, another must necessarily lose. While it might not be explicit and universal, Trump’s ‘understanding’ of trade reveals a classic case of a zero sum mindset: the belief that one country’s gain must come at another’s loss.

During his first run for president in 2016, Trump slammed free trade agreements like the North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as “war against the American worker” and pledged that “A Trump Administration will end that war by getting a fair deal for the American people. The era of economic surrender will finally be over.”

Trump sees the success that countries in Asia and Latin America have had exporting goods to the developed world, while jobs in uncompetitive traditional manufacturing sectors in the United States have declined. This informs the President’s intuition that foreign countries must be taking the United States for a ride. The mere mention of a ‘trade deficit’ sets off alarm bells, not because it’s actually a bad thing but because Trump feels like it means America is losing.

But this is an elementary mistake. For example, over the course of my life, I have accrued a large trade deficit with Tesco. Whether it’s a big weekly shop or a raid of the bakery after a night out, they just keep taking my money and reducing the benefits of me producing my own food! It is obviously ridiculous to suggest that Tesco are exploiting me in some way. Both sides benefit, with me getting my food and Tesco making some money. They are positive sum interactions. Trade deficits merely refer to investment flows and trade patterns.

But there isn’t much to distinguish that logic from Trump’s approach to free trade. Zero sum thinking might be good politics; it appeals to our primal instinct to assume that another person or tribe’s success is coming at the expense of our own. It creates villains, victims, and tribal loyalties. But the application of zero sum economics to trade leads to chaos for which Americans will foot most of the bill.

2019 analysis of the impact of Trump’s 2018 tariff blitz suggests that they cost each household $831 per year on average. Other studies show significant costs to the US economy in the form of higher tax burdens, lower investment, reduced wages in high-value sectors, and reduced consumption.

An illustrative case study is the impact of Trump’s 2018 tariffs on washing machines. Research from the University of Chicago shows tariffs imposed by Trump on washing machines in 2018 raised $82 million for the United States Treasury while causing consumer prices to rise by $1.5 billion overall. Yes, foreign exporters affected by the tariffs lost out but so did Americans. Trump’s tariffs didn’t redistribute from foreign producers to American producers, they just destroyed wealth.

This is because the distinction between ‘worker’ and ‘consumer’ is irrelevant – we’re all both. When tariffs raise prices, workers and consumers suffer because they are the same people. This was also illustrated by Trump’s 2018 washing machine tariff charge. Even where there were some small benefits for some American workers, they came at a much higher cost for the wider population. 1,800 jobs reshored to the United States as a result of the 2018 tariffs cost an average of $817,000 each. Those jobs would not have existed without government intervention and they were propped up by millions of other Americans through taxes, higher prices, and missed economic opportunities in other more productive sectors.

Even then, the consequences for most American producers were negative. 54% of all US imports in 2015 were classified as either ‘capital goods’ or ‘industrial supplies’ which means that they were used by US-based producers to make new products. Increasing tariffs doesn’t just increase the end price for American consumers, but also increases costs for American businesses, threatening otherwise productive jobs and undermining their international competitiveness.

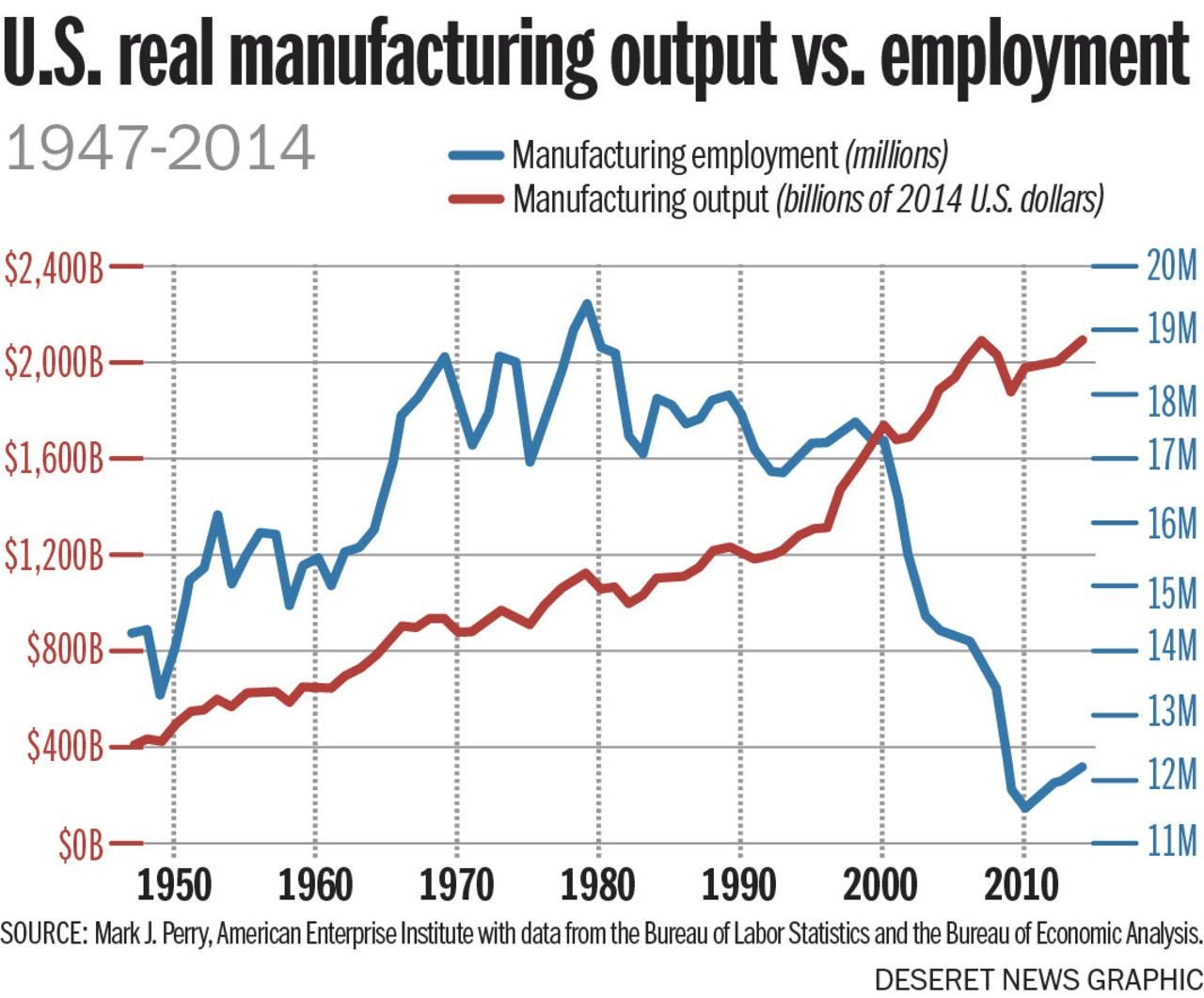

Looking at manufacturing specifically, it is a myth that liberalised international trade has destroyed U.S. manufacturing. It has certainly contributed to manufacturing’s declining share of the U.S. economy and the number of manufacturing jobs. What remains, however, is the second largest manufacturing sector in the world which uses U.S. capital, technology, and skilled labour to manufacture goods higher up the value chain.

Rather than steel forging and coal mining, American manufacturers specialise in creating cutting-edge electronics, chemical products, and medical devices. Manufacturing employment has been declining for decades but productivity and output rose at the same time.

This is where trade is once again mutually beneficial and positive sum. It gives Americans access to cheaper, more abundant goods, while allowing high productivity American producers to purchase inputs from countries which produce them more cheaply and efficiently than is possible domestically. When tariffs are imposed on steel imports, for example, a small group of American raw steel producers may benefit but everyone who consumes products created using steel and everyone working in industries that require steel as an input lose out.

Like all zero sum economic policies, the implementation of trade tariffs starts a cycle whereby demand for more zero sum policies rises to mitigate the negative impacts of previous zero sum policies. One example is that tariffs tend to provoke retaliation from other countries. Although retaliating against tariffs is an act of economic self-harm, it still harms exporters in the country that initially imposed the tariffs. During Trump’s 2018-19 trade war, American farmers lost export markets in Asia and the taxpayer ended up footing the $12 billion bill to bail them out. In this case, American consumers got hit by higher prices, foreign exporters and domestic producers suffered, and taxpayers were forced to support uncompetitive farmers. A lose-lose-lose-lose.

But when trade barriers are broken down, individuals, businesses, and countries can better specialise and allocate productive resources to their highest value use. Consumers get a greater choice of cheaper, more abundant products, domestic producers see the same benefit for their imported production inputs, foreign producers make money, and taxpayers are unaffected. A win-win-win-win.

Of course, there are myriad domestic and international policies which have distorted the idealised vision of free trade laid out above but that doesn’t mean that doubling-down on protectionism is a good idea. Liberalising trade between individuals, businesses, and nations creates positive sum interactions, making everyone better off. Ironically, it is policies influenced by fallacious zero sum thinking that create more zero sum scenarios.

Trump promised Americans that they were going to get tired of winning. Instead, his zero sum worldview risks Americans’ paying more, producing less value, and fighting pointless international battles. If the Trump administration pushes ahead with these tariffs and Congress refuses to limit the President’s authority to impose them, we’re all going to get tired of losing very quickly.

Interesting piece. Yes there are winners and losers in trade wars or competition from cheap labour. But, I think you are wrong. Whether we are an insular economy or a world wide economy there is at any one time a finite amount of money. If someone benefits and profits it will always be at someone or some groups expense by losing the equivalent. It’s just maths. Individual market forces dictate flow of capital and when certain companies may do well others have to fail to equal the equation. The differences only happen when the rules we all learn from a young age play out. That is ‘piggybank’ economics. We all learn that to grow the pot we must add to it and not take any out! Simple but true. The world is full of money but it’s a finite amount so to do well automatically means someone else has to loose. The differences comes when money is printed. (Added to the piggybank) There has to be an equation to quantify this amount. It has to represent the reason why a milkman in the 70s earned £50 a week and if there was one now he might earn £2500 per week. That is the effect in the main of inflation! A need to print the extra requirement. In the same equation we must see that an amount of money printed must represent the needs of say a 2 million population and say a population of 79 million. There had to be a difference. But whatever the equations and whatever the total monetary figure an equal amount is and has to be balanced. What we have to do though, is understand that Trump thinks like a company CEO. He doesn't care about the fall out of his actions as long as he can justify cutting costs and increasing prices to show a profit. But you can’t run a country like that! It’s irresponsible. Those in charge must think in the round to look after all citizens. And frankly no Government thinks in the round as they don’t have any brains to think beyond two sided bookkeeping it seems to me, when they should be thinking in 3 and 4 dimensions! It’s just beyond their experience and knowledge as if promoted to a level of incompetence. As I fear we see Trump and similarly Rachel Reeves seem to be. As nothing makes sense! There is no thought in the round. For examples Income tax and NI is actually paid by the employer not the employee. The employee has no chance to spend it not even to credit the exchequer! So ‘we the taxpayer’ is a misconception in common thinking. The employee pays much more tax by spending and spending all their money means they pay as much tax as they can! Our tax systems rules are that SPENDERS pay the tax! Our tax system is based on money moving when spent. So it has to follow that those who can and thus avoid SPENDING ALL their money actually pay NO tax at all on that unspent amount NONE!…. Even a beggar homeless, unemployable and comatose from drinking a bottle of whisky paid over 73% of vat and duty and contributed to the profit of seller supplier and producer! Thats twice a higher rate tax earner. Whereas someone who doesn’t spend pays and contributes nothing no profit no tax revenue! It’s the rich and wealthy that can avoid SPENDING all their money. So that unused money is uninvolved in any part of our working economy for all the time it is unspent, unused and withheld from our working pot. In the main that is the reason why our working pot is insufficient in weight and flow (3rd and 4th dimensions) to produce enough monthly tax take. Unless that other pot holding all their money unused money is reintroduced to the working pot from which tax is triggered then we will never get out of recession and deficit. We owe now £2,800,000,000,000.00 trillion. How can we seriously expect to grow from that minus situation? And by investment if we are lucky? No! We need surety of SPENDING to make money revolve faster and in a tsunami of flow sufficient for an overflowing tax rake. We have to be thinking in the round using money in, money out, money round and in what time scale ( four dimensions) to see the real potential of our work productivity and for that we need a spending policy to make it happen so it can be autonomous and perpetual without the bewildering and reckless decisions and interventions of the like of Trump and Reeves. We need to put a spend by date on money electronically to make money move to make the poor richer, then make the benefits better and to afford at last enough to pay for say a war machine. But counterintuitively the rich will also be richer but from the spending monthly of their income on what they buy and get for that spending and not from the money itself, presently hoarded from the main majority for days to years and centuries as it is now. We must stop tinkering with a wall of cogs to make it work better. Instead have one cog that works! Start using ALL the money out there for its intended use. As an exchange of work in the now! Earn high but spend it! And ensure its return next month! Not a wish and a prayer. By decree. For all people.