by Damian Pudner

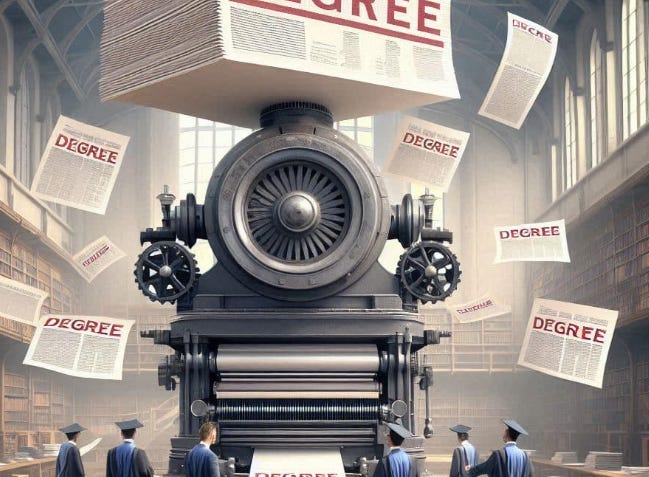

UK universities were once heralded as the beacons of intellectual excellence, places where ideas were rigorously tested and where students emerged intellectually fortified, ready to face the world. Today, however, too many institutions have neglected that mission, prioritising revenue streams and inflated performance indicators over academic integrity. Driven by tuition fees—especially from international students (that account for 40% of English university revenue)—these institutions are increasingly at risk of becoming “degree factories,” focused on financial targets over genuine intellectual growth.

Higher education in the UK was once a public good, free to domestic students with the talent and drive to excel. But in 1998, Labour introduced tuition fees, signalling a major shift. By 2012, the Conservative-led coalition raised the cap to £9,000, with universities increasingly dependent on student income. Labour’s recent announcement to increase fees with inflation deepens this issue, alienating young voters—especially given Sir Keir Starmer’s 2020 pledge to abolish tuition fees, a promise dropped during the recent general election.

In this revenue-dependent model, universities now prioritise student numbers over educational value. Last year, nearly three million students were enrolled in UK higher education, with over a third of 18-year-olds attending. But if students face rising fees, with average debts reaching £40,000-£50,000, shouldn’t they expect more in return?

Introducing true market principles

Ironically, in their universalist approach to ever-higher enrolment numbers, universities have abandoned the very free-market principles that should drive them to excellence. Instead of competing on educational quality, many institutions have opted for a race to the bottom, diluting standards to attract greater numbers. In a true market, universities would compete based on academic merit and the quality of their educational offerings, striving to produce well-educated, capable graduates rather than simply swelling student ranks.

One way forward might be to introduce a flexible, market-driven tuition model that adjusts fees by course type, demand, and potential post-graduate earnings. By linking financial rewards to successful educational outcomes, such a model could encourage universities to focus on employability and high-quality teaching: universities could even offer loans directly to students. Grants or targeted funding could also reward institutions that demonstrate a commitment to rigorous academic standards and tangible student outcomes.

Raising entry standards: quality over quantity

Perhaps the biggest betrayal of standards in recent years has been the lowering of entry requirements. To keep enrolment numbers high, universities have opened their doors to students who may lack the academic foundation for university-level work. While broadening access might sound noble, this approach ultimately dilutes educational quality—not only for underprepared students but for everyone involved. Universities were once prized for their selectivity and intellectual rigour. Today, too many institutions seem more concerned with “filling seats” than cultivating minds.

Raising admission standards might result in a short-term drop in enrolments, but it would ensure that those who attend are genuinely prepared for the rigours of higher education. This shift would allow universities to focus on intellectual development rather than remedial support, restoring the true value of a degree as a mark of accomplishment rather than an award for mere participation.

Combating grade inflation

Grade inflation is another symptom of declining standards in our universities. The proportion of students receiving first-class honours has more than doubled in the past decade, eroding the value of a first-class degree, which is a mark once reserved for the truly exceptional. When everyone is deemed “excellent,” the concept of excellence itself becomes meaningless, leaving employers struggling to distinguish genuine high achievers from average ones.

Universities must tackle grade inflation by restoring rigorous, transparent grading standards. Academic staff should feel empowered to assess students critically, reserving top marks for genuinely exceptional work only. Grades should represent true academic achievement, not serve to boost student satisfaction scores or inflate university rankings. This commitment to integrity will assure students, employers, and society that a university degree continues to reflect high standards and genuine accomplishment.

Reintroducing exams as a measure of knowledge

In recent years, universities have increasingly shifted from traditional exams to coursework-based assessments, a change that has eroded academic standards. While coursework has value, it is more susceptible to plagiarism and lacks the controlled rigour of an exam setting. Traditional exams test students under pressure, compelling them to show resilience, independent thought, and a deep grasp of their subject—qualities essential for success beyond university.

Reintroducing exams as a core assessment method would restore academic integrity and allow students to prove their knowledge. This is not about making things harder; it’s about equipping students for real challenges, where excellence is often forged under pressure.

Universities should challenge, not coddle: ending ‘cotton-wool’ academia

Universities should be preparing students for life, not shielding them from it. Yet in pursuit of high satisfaction scores, many institutions have adopted a “cotton-wool” approach, prioritising comfort over intellectual challenge. This shift has created an environment where resilience and personal responsibility take a backseat to a culture of ease and comfort, leaving students unprepared for the harsh realities beyond campus.

The real world does not shield us from opinions we may consider “offensive”. It demands resilience, critical thinking, and adaptability. Universities should create environments where students confront challenging ideas, learn through constructive criticism, and grow through occasional failure. Shielding students from difficult intellectual challenges may bring short-term satisfaction, but it fails them in the long run.

Upholding the mission of higher education

The fundamental purpose of a university is to educate, to challenge, and to encourage independent thought. If universities continue to operate predominantly like conventional businesses, we risk reducing higher education to a transactional system where students pay for qualifications rather than earn them. That is a betrayal of what higher education should represent.

Universities that uphold high admission standards, enforce rigorous grading, conduct independent assessments, and empower faculty to teach without commercial interference send a powerful and clear message: education is valued here. A degree from a UK university should symbolise intellectual achievement, resilience, and ambition—not just a qualification purchased with tuition fees.

Some commentators blame “marketisation”, but that is a superficial explanation at best. Fitness trainers also operate in a competitive market – but they do not gain clients by devising easy training programmes that shield their clients from having to exert themselves, or by giving them “fitness certificates” which tell them that they are in great shape when they are clearly not. With the right incentives, marketisation can be perfectly compatible with academic rigour.

For UK universities to thrive, they must reject mediocrity and re-embrace the principles of quality, resilience, and intellectual ambition. This is the only way to ensure that a degree from a UK university retains its value—for students, employers, and society alike. By restoring high standards and real competition, UK higher education can once again become a world benchmark and an asset to all who pass through it.

There are two extreme for the style and content of jobs. The first is to work on your own and produce excellent studies of difficult topics. The second is to work with a range of other people and develop and implement results that benefit others.

The problem with degrees is that they train you at most universities to do the former. The problem with jobs is most of them expect you to walk in and contribute to the second. So most degree courses are useless for developing skills at work.

Improving the standard of excellence, while admirable, will not help the average employer, be they government or commercial. I do not think this article is addressing the fundamental of the graduate educational problem.