By IEA Energy Analyst Andy Mayer

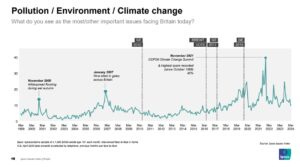

Going into the 2024 general election, Ipsos rated Pollution/Environment/Climate Change at the bottom of their monthly issue index, with the NHS, Inflation and Economy top. Just 3% of the electorate thought it the most important issue, and only 10% thought it worthy of mention at all.

This is not a climate change election – although you would not think this given the attention the issue receives in party manifestos. Nor might you expect this given the issue topped the list of public concerns as recently as November 2021 (40%), during the UK hosting of COP26 in Glasgow. While last month was pronounced as the hottest May on record.

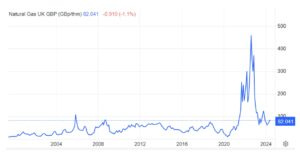

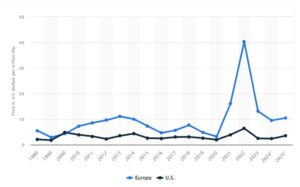

What we may be seeing in the GE 2024 is the vast and ongoing disconnect between elite and public opinion. Energy and climate change is a topic that excites extreme passions in a well-off minority and teenage activists. But it largely bothers the rest of us only when there are real world illustrations, or it burns a hole in our pocket. The latter was a major issue in 2022, given that energy, most materially the price of gas, drives costs in all other supply chains, including those for non-fossil fuel energy generation. Costs are lower now, but still double what they were for much of the previous 25 years.

Polls currently predict a Labour Government in July. The party has traditionally leaned left on these issues, introducing the Climate Change Act when last in power (an architecture for centralised state planning of emissions) and usually setting their targets for decarbonisation more aggressively than those of the Conservatives. Within their manifesto, one of five core missions is to make Britain a “clean energy superpower” by 2030, through a Green Prosperity Plan backed in part by a £7.5bn National Wealth Fund. The language echoes Boris Johnson’s 2020 claim to make the UK the “Saudi Arabia of wind energy”, given most of the achievable renewable capacity comes from offshore wind.

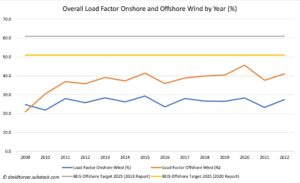

How much, how possible, and at what cost is hugely contested. While growth of renewables in the last two decades has been impressive, leading to it now accounting for 30-40% of power generation annually, it is also unreliable (wind sites only provide energy 25-45% of the time). It is also costly, at on average 2-4 times the normal prices for unabated gas power before carbon charges. New wind sties also require grid expansion and back-up from idle fossil fuel resources, in turn raising their cost. While onshore wind and solar assets require far more land to produce far less energy than fossils and nuclear. These problems increase in line with the share of renewables, making the final stages of grid decarbonisation an exceptionally difficult challenge.

Here, Labour’s ‘yimby’ plans to reform planning and ‘slashing red tape’ may help, if radical and comprehensive, particularly for example for nuclear power. But with current implementation taking 14-17 years versus the world’s best (Japan & South Korea) at 4-6 years, this is unlikely to move the dial on a 2030 target. There is also scepticism about the sincerity of this mission. It breezes over the political difficulty of planning reform (that sank Conservative efforts in 2021), and sits aside manifesto claims to ‘transfer power (including planning) out of Westminster, and into our communities’ (which echoes the Conservatives rhetoric that made reform impossible).

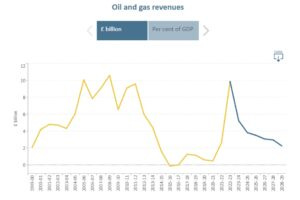

Labour’s other major headline policy is the creation of GB Energy, a state-backed national investment vehicle supposedly part-funded by a ‘proper (North Sea) windfall tax’ and ‘closing (tax discount) loopholes,’ which will ‘crowd-in’ investment to new projects. The numbers are dodgy, £1.2bn a year additional tax predicted (by raising the existing supertax from 75-78%), with £1.7bn additional spending committed alongside a further £3bn for other projects (like retrofitting homes with better insulation) that will require £3.5bn a year of new borrowing.

Raising taxes is more likely to see revenues fall, or possibly go negative which is precisely what happened after the 2006 and 2011 supertaxes. Global oil prices are falling, and Labour’s new site drilling ban will accelerate capital flight.

Meanwhile the main driver of ‘investor confidence’ in renewables is guaranteed returns applied either to bills or taxes – hard cash, not an appeal to partnership or Government stakes. This was illustrated in the most recent rounds of contract bids AR5 and AR6. There was an investment famine after industry costs rose, and feast after a 70% increase in the guaranteed rate.

What GB Energy will do is invest in projects no one else will touch. It might for example revive Swansea Tidal Bay, an venture so awful even the eco-mad Conservative administration of Boris Johnson blocked it (they wanted a 90-year guaranteed index-linked price at a rate twice that of the typical price of gas power). Once revived and part state-owned there will be political incentives to keep the project going, even as costs increase and deadlines are missed.

The risk of malinvestment (wasting money that could otherwise be better spent elsewhere) is high. The stated industrial targets for GB Energy are gigafactories, green steel, carbon capture and storage, and green hydrogen. These are either things in which the UK has little claim to current or future comparative advantage, or, particularly in the case of hydrogen, are predicted to be unfeasibly expensive until the latter part of the century. GB Energy risks being a vehicle for ‘picking losers’.

Their adoption of the Government plan to introduce an EU-style Carbon Border tax in 2027 will add costs to every supply chain, for example making the steel, concrete and plastics required for new homes, insulation, wind, and solar power more expensive.

While new regulations on the Bank of England and large businesses to report on not just their emissions but alignment to the global Paris agreement (which is not binding) will create costly useless jobs for carbon bureaucrats.

The less said about the claim of 650,000 new green jobs, and a British Jobs Bonus for hiring local, the better. Jobs are a cost of doing business, not a benefit, and growth relies on doing more with fewer inputs, not job creation by postcode. When such claims are evaluated, we can find the cost of the subsidies to create green jobs are between £75k-£250k (or more) each, implying the destruction of many jobs elsewhere, not a net benefit.

All these factors speak against a Labour administration being able to ‘cut bills for good’, other than by sleight of hand, moving current green levies onto taxes, and investment plans onto borrowing. Actions which merely hide and delay what will be extraordinary costs and create a vicious cycle - raising the cost of Government borrowing and demands then from industry for higher returns.

Whether their plans can encourage ‘energy independence from dictators like Putin’ is also questionable. Building more renewables would gradually reduce the UK’s exposure to the regional gas price in Europe. But the obvious way to do this much faster would be to expand the North Sea and allow fracking, which Labour would instead “ban for good.” Fracking has enabled the US to keep their natural gas prices well below those in Europe.

Labour’s additional proposals on environmental stewardship and farming are thin. There are nine new National River Walks and three new National Forests, alongside the rewilding of various habitats – projects that find common cause in most manifestos. There is a throwaway reference to a ‘moving to a circular economy’ which, if sincere, would be extraordinarily expensive, requiring the recovery, recycling, reuse, or remanufacturing of all things in all supply chains. Water company executives are to be targeted for punitive removal of their bonuses and may face criminal charges. The Government itself will buy food locally for civil service dinners, which could be a challenge in Whitehall, unless they’re into fried chicken and overpriced pasta.

The main and welcome surprise in the Conservatives manifesto is that after 14 years of hugging huskies, declaring climate emergencies, and hosting private jet summits on reducing emissions their slogan is now ‘an affordable and pragmatic transition to Net Zero’. Much of it is dedicated to their past record. For example:

‘We have reduced emissions further and faster than any of our competitors and the UK is the first major economy to get halfway to net zero. And we have done this while growing our economy by 80%, demonstrating to other countries that there is a positive economic path to tackling climate change.’

However, that amounts to just 29% growth in real terms, at a time when growth in real global GDP has been about 45%. While UK dependency on fossil fuels has fallen about 13 percentage points from 90% to 77% versus a tiny change in the rest of the world (86.3% to 85.4%). A correlation of lower growth with faster decarbonisation does not prove causation (although plausible), but neither does it support the claim that Net Zero has been a free lunch.

The Conservatives in office undermined British fracking with a moratorium, and the case for North Sea investment with a messy 35% bump in tax rates. They intend to continue both policies, increasing UK dependency on imports, which are neither pragmatic nor affordable. Conversely, they provide a marginally more honest account about renewables expansion, noting that this will require new gas power stations.

Like Labour, there are fantasy targets and projects from wind capacity to steel and CCS, alongside made-in-Britain funding promises. There is a major push on nuclear power that cannot be built without major permitting and planning reforms the Conservatives themselves have consistently obstructed, migrant labour from countries with relevant experience that the Conservatives would seek to curtail, and imported energy intensive goods like steel on which the Conservatives would slap a carbon border tax from 2027.

They prefer different sleight-of-hand tricks with energy bills. Local pricing experiments may encourage competition, efficiency, and savings on grid charges, but at the margins, and these costs would be much lower regardless if the pace of change was not being forced by targets. Their pledge to not introduce new green levies, while welcome, is no comfort if the level of the existing mess of charges keeps rising.

Their commitment to retain the energy price cap, meanwhile, speaks to wilful economic illiteracy. Price controls do not work. They just mask the price signals that encourage energy saving and investment. They are either so high as to be irrelevant (what economists call a non-binding price cap), or so low as to curtail supply (a binding price cap). The initial experiment destroyed 70% of the UK’s retail energy companies, undermined price competition, and put the taxpayer and billpayer on the hook for the dregs.

Their most bizarre idea is to nationalise something the internet does for free by introducing a state-run price comparison scheme for petrol pumps (Pumpwatch). Their most dishonest one is a pledge to install underground power cables ‘where cost competitive’ – noting that burying them costs 5-10 times as much as pylons. Their voucher scheme for energy efficiency home improvements conversely seems more sensible than the complex central planning approaches of their rivals. While ongoing investment in flood defences seems wise. There is some further good news in the deregulation of planning for the planting of trees, even if this won’t help young people find somewhere to live.

Pre-coalition, the Liberal Democrats published a pamphlet called “Wasted Rainforests” criticising their own tendency to produce voluminous quantities of policy papers which were never read. Their 117-page manifesto is merely the edited highlights, and to read it is to know suffering, particularly given most of the chapters have some link to environmental policy.

Happily, most of the main proposals, bar different labels, are indistinguishable from those of the Conservatives and Labour. Unfortunately, where there are differences, they are decidedly more statist, anti-market, and delusional on the costs. The orange party wants Net Zero 5 years earlier in 2045. They would tie UK environmental standards to EU standards, whether or not harmful to UK growth or irrelevant to the UK ecosystem. They would, where possible, go beyond these standards to be the highest in the world, whether or not proportionate to the harm being mitigated.

These are costly principles rooted in naïve belief that more standards mean better standards. They are a denial of public choice that exclusionary standards are often linked to the commercial and political chicanery of interest groups rather than the public good. On which score they would deliberately sabotage recent trade deals with Australia and New Zealand to the cost of British consumers at the behest of lobbying by the National Farmers Union.

However, if your highest priority is to ensure that your local lake doesn’t have anything so unsanitary as a party leader floating in it, having fallen off an oil-based floatation device, in consequence of poor standards of training in the use of polyethylene paddles, this may appeal.

Where Labour would require companies to publish Paris-aligned climate plans the Liberal Democrats push for a general duty of care to protect the environment and human rights in both their own operations and supply chains. Hitherto you may not have considered a need for bog-brush maker or pet insurance underwriter to be nature positive, expert in the UN Convention on the prevention of torture, or familiar with scope three emissions for imported bristles.

However, under this rule a new industry of box-tickers would be created compile data and waste further rainforests publishing reports even less read than the manifestos. This would not help UK competitiveness. It would make little difference to companies where such concerns are core to what they do, such as the providers of environmental services, who go beyond these requirements regardless. But it would be helpful to black market traders in other industries utilising the evasion of the regulations as a source of advantage.

British industries that have not been successfully euthanised with green tape, might be banned outright (coal mining, foie gras, caged hens, domestic flights, puppy & kitten smuggling, new airports, single use plastics), crippled by price controls (buses, trains, car insurance and petrol), hit with a one-off retrospective windfall tax (North Sea), a requirement to put solar panels on their roofs (regardless of cost), a national food strategy (regardless of the contribution of imports to food security), or rendered unviable by being compelled to buy electric fleet vehicles in 2030 (regardless of range, utility and cost). The lowest indignity again is reserved for water companies who will be required to put Just Stop Oil protesters on their board.

If any of this causes unemployment among those of us who are not Just Stop Oil protesters, fear not, for the Liberal Democrats have an industrial policy strategy for “Investing in rural and coastal infrastructure and services, including local abattoirs, so that communities are viable and can attract and retain workers, particularly from younger age groups.”

The Green party, having been criticised recently for attracting more far-left activists than environmental ones as Labour returns to the political centre, surprise by making their main energy policy one of which IEA authors typically approve: a proposal to introduce a UK Carbon Tax proportionate to the emissions produced. This, if applied consistently across an economy, would be the most efficient way of using market forces and the price mechanism to internalise the social and environmental costs of emissions. The party would also end the importing of biomass to burn at Drax, a high carbon con in receipt of public subsidies, a view again supported by an IEA author.

The relief doesn’t last long. The level of their proposed tax starts at £120 per tonne of CO2. This is three times the level implied by the current UK ETS (under which the requirement to buy carbon permits acts as an implicit carbon tax), and twice that in the EU. Worse, it will rise to £500 within a decade. The initial mirth that greeted this proposal, in essence that the Greens had announced a halving of fuel duty (currently equivalent to about £240), would be short-lived, by 2034 it would have doubled. This would be devastating for those reliant on their cars for work, yet unable to afford an EV upgrade. The halving would also be unlikely. A Green government would claim fuel duty is a multi-dimensional eco-tax covering climate, air pollution and congestion. In reality the future rate could more than triple on that basis, with wider economic damage from the high rate.

Their home building programmes is the most expensive of all, requiring Passivhaus standards (net zero or net negative) for new build and heat pumps in addition to compulsory solar panels. This could add £41k to £63k to the average cost of a typical home (+16-24%). Retrofitting homes to higher standards would be done on a community-by-community basis, which would be more efficient, but suggests no opt-outs, and in many cases would be pointless, the gains in energy efficiency to be made are slight and not worth the tens of billions being spent to achieve them. Doing all this would further defeat the purpose of a carbon price, which should nudge homeowners towards the same end, but when they are ready, and the products are better value.

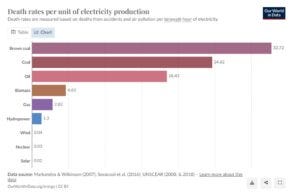

Green opposition to nuclear power has always been ideological and linked to nuclear weapons. There is a perfectly rational basis for opposing nuclear projects like Hinkley Point on cost grounds – they are way over budget, and no one else wants to buy the defective EDF technology. Outright opposition on bogus safety grounds, however, denies the UK access to the only stable source of low-carbon power at scale. Nuclear is brilliant as baseload (the energy required in summer) and needs between 50-300 times less land to deliver it than renewables. More sensible net zero plans see it fulfilling a fifth to a third of our generation needs.

In consequence, their aims for the expansion of renewable power are the most ambitious, setting targets like 80GW of offshore wind capacity by 2035 versus 50GW for the current Government. Again, the logic of carbon pricing escapes them: the whole point of carbon pricing is to obviate the need for such schemes. Once you have a rising carbon price, such investments will automatically follow, at scale. A target is the, at best, irrelevant, and setting one for a particular technology distortionary, unless merely a best guess. Let the market deliver the best renewables first and worry more about making it cheaper and easier to do so by deregulating planning and environmental permitting standards.

Their overall cost estimate for the low carbon transition is £40bn a year, higher than Labour’s original ambition of £28bn and much higher than the single digit commitments made in their manifesto. The Greens plan to meet this with a wealth tax speaks to little understanding of how ineffective such taxes have proven to be elsewhere, and the avoidance behaviour they encourage that destroys much of the value governments believe they can extract.

They would also spend £30bn nationalising water and large energy companies. This would create no benefit, and merely put the taxpayer on the hook for what would now be less efficient protected national champions. The key to better regulated monopoly performance on the environment is incentives not ownership.

The Plaid Cymru manifesto is very similar to the Liberal Democrat, Labour and Green manifestos combined but with a Welsh accent and much dottier target to achieve Net Zero in Wales by 2035. Their national energy company Ynni Cymru would focus on community energy development, and they want Westminster to pay for some of it through reparations for coal mining.

At the time of writing the SNP manifesto was still not out, although it promises to be 'the most left-wing', except on the North Sea, where it is expected to reverse a previous commitment to a ban. We have not reviewed the Northern Irish parties.

Reform’s 'Our Contract with You' is arguably the only mainstream party manifesto to go against the elitist grain on climate change, although the continuity SDP would disagree. They believe ‘Net Zero has sent energy costs soaring… making us poorer and colder, damaging British industry and forcing drivers off the road.’ They would scrap energy levies (although do not explain how they would exit the contracts and projects these currently fund) and ‘global’ Net Zero targets and regulations. They would fast-track drilling in the North Sea, small modular nuclear reactors, and permit fracking on test sites for 2 years (which is surprisingly weak). They would cut fuel duty by 20p (-38%), VAT on energy bills (-5%), and reduce corporation tax first to 20% then 15% in 2027. They would scrap ULEZ, low traffic neighbourhoods, bans on petrol and diesel cars, 20mph schemes, and the Zero Emissions Mandate (forcing car makers to sell rising quotas of EVs).

While generally pro-deregulation and lower taxes, the manifesto has many statist elements, for example, they would raise employer’s national insurance on foreign workers, which would damage some of these ambitions. They would put 50% of energy companies into public ownership with the other half owned by pension funds, which is to the left of Labour on their ‘GB Energy’ proposal.

They would scrap climate subsidies for land use but return to direct payments for food production at a higher cost, impacting the price of food. Their ‘buy British’ scheme would further raise the cost of providing public services. They agree with the left parties on restricting single use plastics, and the Conservatives with planting trees. Like those, they have an industrial policy plan, but with different targets. They would incentivise lithium mining (battery supply chain), gas power turbines, synthetic fuel, tidal power and coal mining. They would reform some planning rules, but only on brownfield sites.

On energy and climate there is then no mainstream classically liberal or libertarian party in the UK race (although the actual Libertarian Party UK claim that Reform nicked their Net Zero policy from their 2019 Free States manifesto). Each of the parties likely to have seats in the Parliament are to varying degrees borrowing from a number of traditions, as we might expect.

Reform come closest to any of the parties in taking the cost of Net Zero seriously, but may have under-estimated the difficulties attached to reducing those costs, while adding some of their own through industrial strategy, hostility to migrants, and anaemic planning deregulation. Both the Conservatives and Labour Parties are engaging in cakeism, talking up the power of green innovation to bring benefits while hiding the costs. While the rest are to varying degrees going to limit their ambition by introducing expensive regulations that enable communities to block change.

It seems unlikely then that the UK will enter the next election having resolved energy security affordably or with much progress on decarbonisation. It seems certain however that there will be many more state jobs created claiming the opposite is true, and that bills will continue to rise.