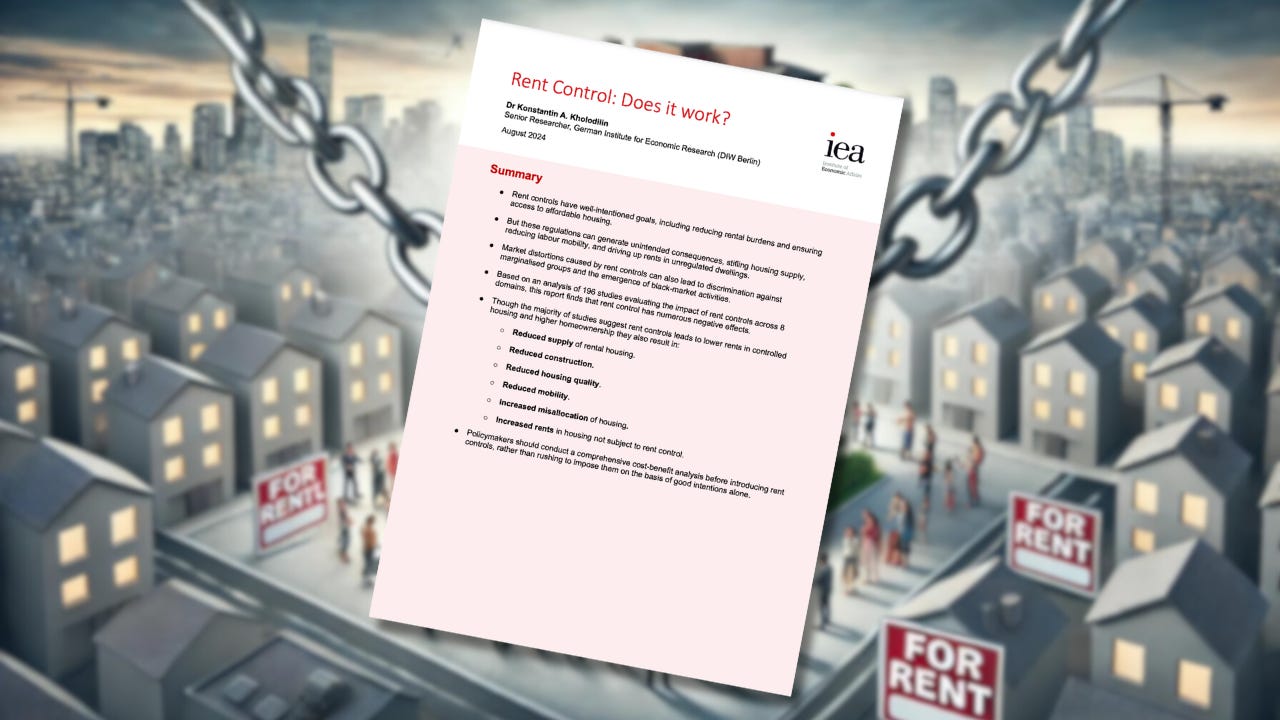

Rent Control: Does it work?

The overview highlights the academic consensus on harmful consequences.

By German Institute for Economic Research Senior Researcher Dr Konstantin A. Kholodilin

Most studies (56 out of 65) find that rent controls succeed in lowering rents for controlled units, as intended.

However, 14 out of 17 studies found that rent control leads to higher rents in the uncontrolled sector.

12 out of 16 studies found negative effects on housing supply, while 11 out of 16 studies found negative impacts on new construction.

15 out of 20 studies found rent control leads to reduced housing quality and maintenance.

25 out of 26 studies found rent control reduces residential mobility.

All 14 studies examining the issue found rent control leads to misallocation of housing.

A new briefing paper from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) provides a comprehensive global overview of the empirical evidence on rent control policies, finding that they produce significantly more negative consequences than benefits.

This briefing comes as calls to introduce rent controls in Britain have mounted in response to the housing crisis. London Mayor Sadiq Khan, a recent Labour-commissioned report, and the Green Party have backed the idea. Scotland had a rent increase cap until March 2024, and tenants can still challenge some increases.

Rent control involves the government setting the price for rent, usually below the market value. The paper, authored by Dr. Konstantin A. Kholodilin, Senior Researcher at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), reviews 196 studies undertaken over 60 years. They span almost 100 countries in all inhabited continents.

The briefing paper highlights the strong and enduring consensus in the academic literature about the impact of rent control. Namely, according to Kholodilin, rent control benefits existing tenants at a significant cost to the broader society.

This leads to less maintenance spending, conversion to owner-occupation, and the construction of fewer new properties, ultimately exacerbating a housing shortage. This week, reports emerged about the rental supply in Buenos Aires jumping by 195.2% following Argentina's President Javier Milei's repeal of rent control laws.

According to Kholodilin, rent controls can also create ‘excess demand’ for housing. This can result in new residents finding it difficult to locate places to live, which decreases labour mobility, increases discrimination against marginalised groups, and boosts black market activity.

The policy can also result in people staying in their existing apartments for longer than they should, such as a widower remaining in a large rent-controlled apartment long after her family has moved out. The lack of movement leads to a ‘misallocation’ of available properties, resulting in further economic damage.

Dr Konstantin A. Kholodilin, paper author and Senior Researcher at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin), said:

“Rent control effectively reduces rents in the controlled sector, but does it a high price. Tenants occupying the rent-controlled dwellings benefit the most, at least in the short run, while newcomers lose from rent control. In the long run, rent control can undermine the rental sector forcing landlords to convert their dwellings and tenants to become homeowners.”

Dr Kristian Niemietz, IEA Editorial Director, said:

“Economists are a notoriously divided profession: ask three economists, and you get four opinions. But there are exceptions to this, and the study of rent controls is one of them. This is an area where the empirical evidence really overwhelmingly points in the same direction. The finding that rent controls reduce the supply and quality of rental housing, reduce housing construction, reduce mobility among private tenants, and lead to a misallocation of the existing rental housing stock, is as close to a consensus as economic research can realistically get.”

Ronan Lyons, Associate Professor in Economics, Trinity College Dublin, said:

“Dr Kholodilin’s comprehensive review of the rent control literature is tremendously helpful, not just for academics but also for policy analysts and policymakers, as numerous cities across the high-income world grapple with housing shortages.

“The resurgence in rent controls over the last decade is, given the affordability challenge in housing, perhaps politically understandable. But, as Konstantin’s thorough overview shows, the economic costs of such policies can be significant. Armed with the key facts marshalled by this review, policymakers can make better informed decisions on rent affordability policies.”