By Phillip W. Magness, David J. Theroux Chair in Political Economy at the Independent Institute.

Karl Marx’s influence among intellectual elites underwent a massive rebound in recent years. In 2018, mainstream publications including the New York Times, the Economist, and the Financial Times ran gushy homages to the communist philosopher to commemorate the bicentennial of his birth. Marx’s Communist Manifesto consistently ranks as the most frequently assigned book on university course syllabi, with the exception of a few widely used textbooks. Bibliometric evidence of Marx’s prevalence abounds in academic works, where he consistently ranks among the most frequently cited authors in human history. The academy erupted with yet another fanfare for Marx last month, when Princeton University Press released a new translation of his magnum opus, Das Kapital.

The high level of Marx veneration in modern academic life makes for a strange juxtaposition with the track record of Marx’s ideas. The last century’s experiments in Marxist governance left a trail of economic ruination, starvation, and mass murder. When evaluated on a strictly intellectual level, Marx’s theories have not fared much better than their Soviet, Chinese, Cambodian, Cuban, or Venezuelan implementations. Marx constructed his central economic system on the labour theory of value – an obsolete doctrine that was conclusively debunked by the “marginal revolution” in economics in the 1870s. Capital was also riddled with internal circularities throughout, including its inability to reconcile the pricing of labour as an input of production with labour as a priced value onto itself. By the turn of the 20th century, Marx’s predictive claims about the immiserating forces of capitalism were confronted with the tangible reality of growing and widening levels of prosperity.

By every measure of its own merit, Marx’s economic system should have been relegated to the dustbin of intellectual history – and for a brief moment it was. Marx’s Capital struggled to find an audience in his own lifetime. He died in 1883 in relative obscurity and with little following outside of a small band of fanatical leftists led by his friend Friedrich Engels. Even among fellow socialists, Marx was a controversial figure. He spent the last decade of his life locked in endless internecine feuds with anarchists, non-revolutionary socialists, and even other competitor revolutionary factions. For decades after his death, he faced credible accusations of plagiarising his theories from other writers. The Manifesto has more than a few arguments that strongly resembled an 1843 pamphlet by French socialist writer Victor Considerant, and Marx’s doctrine of “surplus value” closely follows an earlier work by democratic socialist thinker Johann Karl Rodbertus.

When mainstream economists first noticed Marx’s work in the years following his death, they made mincemeat of his doctrines over their aforementioned contradictions. Alfred Marshall, in his 1890 textbook, described Capital as an exercise in circular reasoning “shrouded in mysterious Hegelian phrases.” When John Maynard Keynes assessed Marx’s works in 1925, he dismissed Capital as “an obsolete economic textbook […] without interest or application for the modern world.”

So how did the little-known author of a panned and discarded book become one of history’s most cited and influential thinkers over the course of barely a century? Michael Makovi and I set out to investigate this question using data gathered from the massive Google Books scanning project, which aims to digitise leading university library collections from around the world. In doing so, we took up a theory posed by dozens of thinkers from across the political spectrum. In this telling, the communist thinker owes his reputation not to the internal salience of his ideas but to a chance event, the Russian Revolution of 1917 that was carried out in Marx’s name. Philosopher Alan Ryan succinctly summarises this view in his 2014 study of Marx:

“If the German Government had not sent Lenin across its territory and back to Russia in a sealed train in early 1917, we might today regard Marx as a not very important nineteenth century philosopher, sociologist, economist, and political theorist.”

Ryan is only the latest in a long and distinguished list of scholars who have entertained similar notions. Frederick Copleston’s monumental History of Philosophy posited that the Soviets “saved Marxism from undergoing the fate of other nineteenth century philosophies by turning it into a faith.” Non-Marxian socialists G.D.H. Cole and H.G. Wells expressed similar views in the aftermath of the Bolshevik upheaval, as did the Marxist thinker W.E.B. Du Bois. Among free-market thinkers, Ludwig von Mises and Thomas Sowell have both made similar observations. More recently, Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm contrasted the limited distribution of Marx’s texts in the decades after his death with the period after 1917, when formal instruction in Marxist theory came to benefit from the “unlimited resources of the Soviet Communist Party.”

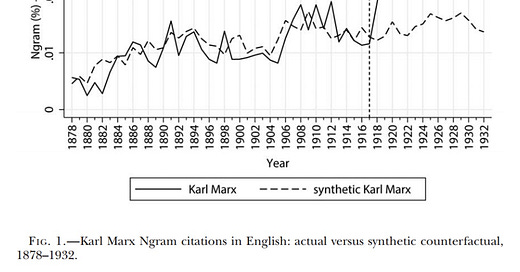

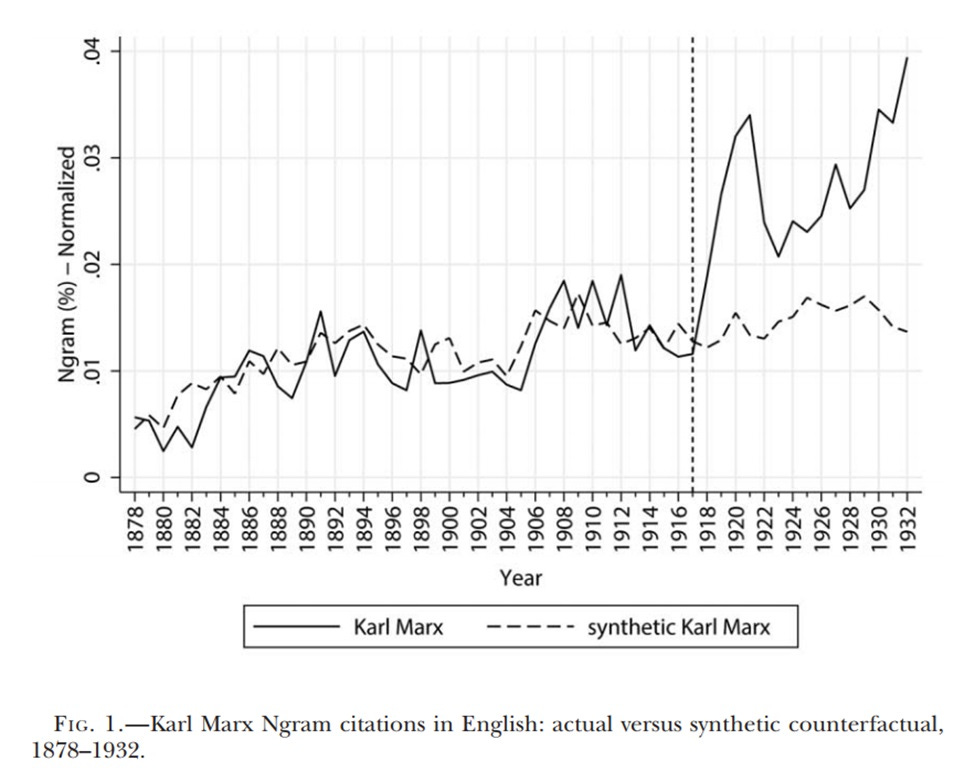

Our proposed test of the Soviet effect on Marx’s reputation is straightforward. Using the Ngram reader tool, we can determine the frequency with which Karl Marx’s name appeared in printed works relative to all other books published in a given year. We may do the same for almost any other author, ranging from the most famous names of antiquity (Plato, Aristotle) to now-obscure socialist contemporaries of Marx from the 19th century (Ferdinand Lassalle, Mikhail Bakunin). In total, we scraped annual citation references for some 225 other figures who preceded or overlapped with Marx’s life. Using an econometric approach known as Synthetic Control, these other names were matched and selected by statistical software for their similarities to Marx’s citation patterns prior to 1917. The composite result yields a “synthetic” counterfactual for Karl Marx’s citations by projecting what their trajectory would have been had the Russian Revolution of 1917 never happened.

Our results confirm the long-hypothesised effect of the Bolshevik upheaval on Marx’s reputation. In the decade after 1917, Ngram references to Karl Marx tripled vis-à-vis their pre-revolutionary baseline. The pattern continues like a hockey stick to the present day.

We first published these results in a 2023 study in the Journal of Political Economy, and have since extended them to tests in other languages such as German, and in other parallel databases such as English and German-language historical newspaper scans. In all of our testing, the results point to a clear and empirically robust finding: the Soviet Union put Karl Marx on the intellectual map.

Note that we do not claim that Marx was unknown prior to 1917. His works gained a following on the far-Left periphery, and attracted harsh criticism from economists who read them. But Marx’s extremely high stature as an intellectual today came from his elevation by Lenin and his comrades. In an alternate universe absent the Soviets, Marx might still be studied as a specialised academic niche – perhaps one of a half-dozen or so 19th century socialist competitors. Instead, he ranks as the preeminent socialist thinker and one of the most influential thinkers in human history.

This finding should not be surprising. Even devout Marxists such as Hobsbawm anticipated it in their work. Yet it also carries an unsettling implication for devotees of the socialist philosopher, as it inextricably links Marx’s name and modern salience to the political legacy and humanitarian baggage of the Soviet Union.

When we first published our results, we expected some degree of controversy from modern-day Marxists who wish to dissociate themselves from the crimes of Lenin and Stalin. Academics in this camp have predictably raged and flailed against our work, insisting that anecdotal citations of Marx by another author in the 1890s or early 1900s (which were already captured in our data from Google books) somehow undermine our findings. Others insist that the Ngram database is somehow biased against Marx, which would necessitate an implausible scenario wherein library scans undercounted his name before 1917 only to suddenly capture an accurate count in all years thereafter. For this proposition to hold, all other authors in our database would also need to be unaffected by this speculated bias – a similarly implausible outcome.

We have nonetheless endeavoured to answer our critics through subsequent investigations of their claims. For example, some Marxists have speculated that the adoption of a Marx-inspired platform in 1891 by Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) led to a pre-Soviet popularisation of Marx’s writings in German-speaking regions. We tested this theory by restricting our data to German-language Ngram citations, and constructing a parallel database of author mentions in German-language historical newspaper scans. We found very little evidence of a pre-Soviet boost to Marx’s citations from the SPD though. Indeed, German texts follow the English-language pattern from our main results. These findings will be published in a forthcoming article in the Southern Economic Journal next year.

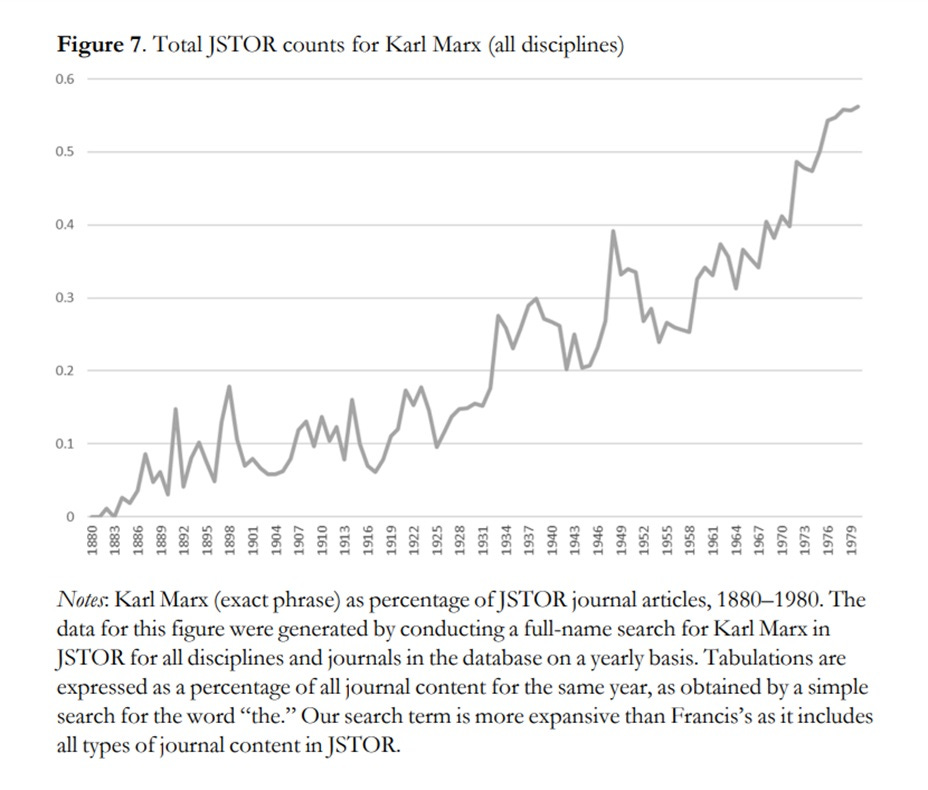

We also recently answered a critic who attacked the very premise of using empirical measurements to study intellectual history. In this investigation, we calculated Marx’s citation patterns in the JSTOR database of academic journals, finding a nearly identical pattern to the Ngram book scans where Marx remains relatively flat before 1917, then skyrockets after the Russian Revolution. By contrast, our interlocutor’s data do not support his claim that Marx was highly influential in the late 19th century, and his qualitative survey of the literature is at odds with a wide range of writers from Mises on the free-market end to Hobsbawm and Alain Badiou on the Marxist far-Left.

On the other side of our critics on the Marxist Left, a number of authors have conceded the validity of our empirical findings only to follow by insisting that they are banally true and obvious. This faction questions why the Soviet role in boosting Marx even needed to be measured, let alone subjected to advanced econometric analysis.

While I welcome these acknowledgements of the validity of our results, I also submit that they reveal the answer. Marxists remain divided over their own connections to Lenin and the Soviet Union. Some accept this legacy as an obvious and regrettable historical fact, while others run from it and posit an alternative dissemination mechanism for an intellectual Marxism that claims to be untainted by the famines, massacres, and Gulags of Soviet practice. In doing so, they unwittingly reveal the necessity of our study as it resolves the Soviet question surrounding Marx’s legacy. It remains true that Marx inspired Lenin, another revolutionary from the extreme political periphery. But Lenin seized on a chance event from history and, as the beneficiary of both luck and his own willingness to engage in unscrupulous tactics, turned Marx a household name. By implication, the intellectual edifice of academic Marxism today owes its salience – and very existence – to the catastrophic events of 1917.

Recommended reading: “The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence” | Phillip W. Magness and Michael Makovi | Journal of Political Economy 131(6)